Biographical Details

Date of Birth: October 5, 1811

Birth Location: Liberty, IN, USA

Graduation Year(s): 1837

Degree(s) Earned: Bachelors

Date of Death: August 21, 1874

Death Location: Keokuk, IA, USA

Date of Birth: October 5, 1811

Birth Location: Liberty, IN, USA

Graduation Year(s): 1837

Degree(s) Earned: Bachelors

Date of Death: August 21, 1874

Death Location: Keokuk, IA, USA

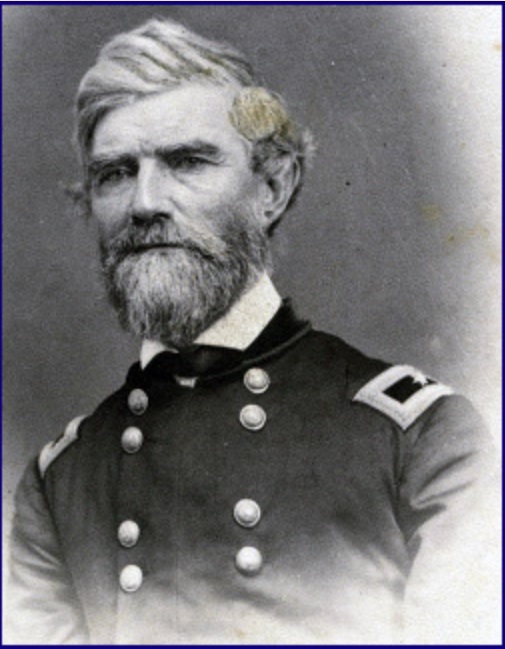

Hugh Thompson Reid was born in Liberty, in the Indiana Territory. He was the elder of two brothers. He was educated at Lane Seminary near Cincinnati, Ohio, and at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. He graduated from Indiana College (now IU) in 1837. His classmate, Richard Holman, wrote that Reid was a shining light among his peers, “as sunny spots on the cheerless waste of time...a friend – not one who impelled by motives of interest has sought and obtained my friendship, but from the purest, holiest motives. Oh it is sweet, to turn from the cold and lifeless formalities of the world...and bask in the sunshine of the friendship of such a man as Reid.”

Reid moved to the Iowa Territory in 1839. He became a prominent attorney-at-law in Fort Madison and Keokuk. From 1840 to 1842, he was the prosecuting attorney for five counties. At one point, he was Iowa’s largest landowner. He became district attorney for the Iowa Territory and was a successful land lawyer.

Reid was Joseph Smith’s hired defense lawyer until the Mormon leader was assassinated in 1844. Iowa gained statehood in December 1846. He was president of both the Des Moines Railroad Company in Keokuk, and the Hamilton Bridge Company. He was considered the primary builder of the railroad through Iowa, which ran from Keokuk to Fort Dodge. Work was halted on the railroad during the Civil War, but it was finally completed in 1870. During these active years, Reid’s biographers wrote that he was “a man of energy,” strong-willed, tireless, “stern, exacting,” “a terror,” rarely failing to convict, having “an iron will and persistency,” and working “with sleepless vigilance, traveling much on railroad at night,” such that “he had little time for social intercourse and made few confidents.”

Reid’s military career was short but distinguished. He was a visitor to the West Point Military Academy. He enlisted in the Civil War at age fifty, and he served as a colonel of the 15th Regiment of Iowa Volunteers. At the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, a metal ball passed through the right side of his neck while he was astride his horse. He fell to the ground and appeared dead. Motionless to onlookers, his body was recovered and taken to the rear of the battle. According to his eulogist, at that point something miraculous occurred as he regained consciousness, “recovered and remounted; continued in command, riding up and down the lines, covered with blood, exhorting the men to stand firm; being the last mounted field officer who remained on horseback to the close of the battle.”

In October, Reid was still ill from his wound as he fought in the Battle of Corinth. While commanding the port in Columbus, Kentucky, he caused the arrest of the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC). The KGC was a racist secret society whose objective was to create a “golden circle” of slave states across the U.S., Mexico, and Central America. He also gave information to Admiral Porter that led to the Union capture of Yazoo City, Mississippi.

Reid commanded a series of military posts in Cairo, Illinois; Post Bolivar, Tennessee; and Lake Providence, Louisiana. He took part in the following Civil War battles: the Battle of Hatchie, the Battle of Corinth, Mississippi, and the Battle of Providence, Louisiana. He was a member of the Society of the Army of Tennessee. In 1863, upon Ulysses Grant’s recommendation, Reid was promoted by President Lincoln to brigadier-general with the unusual distinction of unanimous confirmation by the Senate without having it go to committee.

Reid commanded a brigade that consisted of both Black and White soldiers in Louisiana. At a time when colored soldiers were disparaged even by their Union colleagues, as William Belknap wrote, “he was among the first to favor the enlistment of colored troops, and when some of his Regiment objected, in vigorous words he spoke to them and reminded them in language which went to the mark: ‘Remember that every colored soldier who stops a rebel bullet saves a White man’s life.’” Although such a quote might cause readers to flinch today, at the time, it was considered a bold and unconventionally liberal appeal for racial equality.

After the Civil War, Reid tried to resume his law and railroad businesses, but he had to retire due to his war injury. Two years before his death, he became a church member and was confirmed by Bishop Lee. He was a vestryman in St. John’s Episcopal Church. He spent more time with his family and religion. He suffered a series of strokes, in addition to the paralysis induced by his neck wound, and he developed Bright’s disease of the kidneys. He eventually fell into a coma and died two days later. He left behind his wife and three sons (the youngest age ten).

Reid’s eulogist wrote that “indulgent toward his family, to them he was ever kind and affectionate; his goodness of heart being proverbial, for his heart was as tender and sympathetic as that of a child. . .unsullied by the breath of scandal, and untarnished by the words of reproach.”

Reid married, but his wife died in 1842. Around the same time, his father remarried and had another son and daughter. After retiring from the practice of law, Reid married Mary Alexine LeRoy of Vincennes, Indiana. They had three sons, James, Alan, and Hugh Jr.; the last was born in 1864. James had a son who lived three months, and a daughter Mary Alexine who was blessed with 11 grandchildren by the time she died in 1954. Five of her descendants would go on to graduate from Indiana University, as of 2020. One of these met her husband at IU, being the wife of IU Swim Team Captain Tony Anderson, who swam in three IU Big Ten Championship teams and was a double Olympic Festival gold-medalist.